Featured image by Timi Honkanen

Anilins

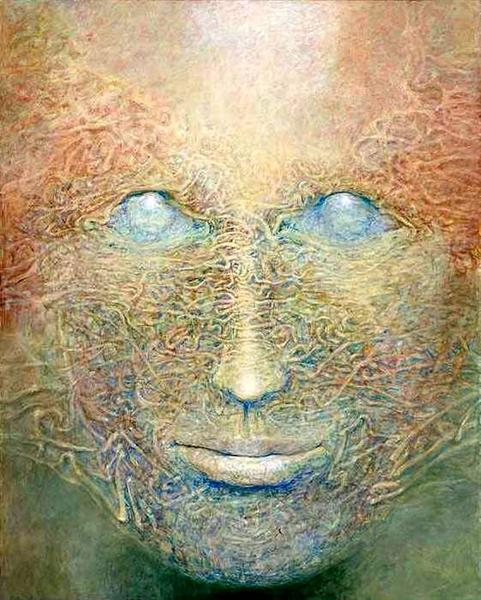

From a distance, they are indistinguishable from human children, not older than twelve. The only noticeable difference is their long, thick hair that will usually fall below their knees. They are furtive and rarely seen up close, as they have little truck or fellowship with men, but in the event one may also notice their dark eyes, and the webs of white lines criss-crossing under their skin. They are perhaps most famous for their strange lifecycle. They live long lives as children for ninety-odd years, growing to their ‘juvenile’ form at the rate of human children, before aging to a rarely-seen adulthood, bearing children, and dying within three to five years. All the anilins in a birthgroup-clan are naturally near enough the same age, and proceed into adulthood and death at exactly the same time.

The anilins have no conception of family – parents and children, brothers and sisters, nor even boy and girl – beyond their clan identification, and their communes formed of two or more clans. The tribal structure reduces the risks inherent in the anilin lifecycle, as a single clan would find anilin infants without adults to rear them. The communes hold all things in common, but each clan acts separately elects their own ‘Speaker,’ a chieftain-like position responsible for communicating with other clans and outsiders, decision-making remaining the domain of the whole community. Anilins usually only reproduce within their clans of a hundred or so, and they’re (mostly) immune to the effects of inbreeding, but the incest combined with their black-eyed-child appearance means they squick most humans out.

Anilins are also all telepathic, and communicate with each other telepathically. For this reason, they don’t have any spoken language and most anilins are effectively mute. They usually understand the languages of the humans living closest to them, because if any of them understand it, the rest will learn it passively over time. They do have telepathic “languages” that include analogs to symbolism and grammar, but all anilin languages are mutually intelligible. Their telepathy averages about a mile radius, but their trained scouts and hunters can send their thoughts ten miles away.

Their abilities are magnified by the presence of other anilins. All the anilins in a clan or commune can communicate to places continents away or strike fear into invaders’ hearts – most of their forests appear cursed because of this. Some clans can perform acts of obvious magic when gathered together, but this tires and sometimes kills them. In times long past, a sufficiently large gathering of anilin clans could warp reality (as Wish) at the cost of all their lives. Presently, too few remain for such a feat to be realistic. Sometimes two anilins, by dint of birth, have such a strong telepathic magnification on each other that they can cast psionic spells. These “twins” needn’t be directly related to each other, but once identified, they are treated as the same person by the commune forever afterward. Their powers increase as they become more alike in mind and purpose.

Their communes are all hidden. The population is centered on the commune-proper, usually nestled in the best-hidden and somewhat centrally located part of their domain. These structures are typically built out of clay-mortared irregular stones, though building styles can vary greatly. They will also reuse abandoned ruins without major alterations to stonework, if they deem it ‘hidden’ enough. The commune is the long-term residence of all the anilins – they don’t spread their population out at all. They most often practice forest husbandry, and under their careful hands the wilds bear more fruit – figs, most commonly – than the arborist’s finest orchard. Groups of anilins are periodically sent out to gather the bounty of their lands, and they occasionally build a few structures outside the commune to house these parties. More often, they’ll simply use natural or temporary shelters, and those that they deign to construct falls within the lines as nature provides. Smoothed caves, tree-top platforms, and smials are there habit. Most people will pass straight through a commune’s groves without noticing. They also hunt and are famous for keeping bees for their honey and wasps for larva and war.

Few human polities maintain diplomatic, tributary, or economic ties with communes, simply because few are aware they’re present. The awareness of the nearest human settlements to a commune ranges from ‘creatures of myth’ to ‘intermittent trade contact’ depending on their history. In times past, anilin communes were integrated into the feudal, imperial, or republican power structures of human polities. These days there’s so few of them and the land they occupy is so isolated and marginal (for human use) that few kings or princes find it worth the trouble to conquer them.

On the subject of personal combat, the most an anilin can hope to do against an adult human is stick a knife between their ribs. They’re not any stronger than a child, and in fact more vulnerable as their long hair is actually a living and vulnerable part of their body. Pulling it will cause excruciating pain, and cutting it will kill them – if they’re lucky. An anilin without their hair loses their telepathy, to them a fate worse than death.

However, an anilin army is an entirely different beast. Their weapon of choice is the sling, their bows being too weak for war. They go to war as shield-bearers, setting down their great pavises for cover and then firing terrifying hails of stones, or hollowed projectiles that scream as they fly overhead. Because of their telepathic communication, they have far greater tactical flexibility and knowledge of the battle’s developments, and they almost never rout but retreat in good order once they agree that the battle is lost. They rarely use their magic on the battlefield, as it is subtle and tires them, but when forced to they will terrify their enemies to drive them from the field. A clan of anilins is worth more than most human regiments in war, but they are neither martial or numerous and rarely form armies.

Anilin adulthood is a short and brutal affair. Their hair begins to fall out, and the white nerves that criss-cross their skin will blacken. Sickness, infirmity, and memory loss follow. After the necessities of reproduction are taken care of, the clan adults generally prefer to seal themselves inside a tomb in an act of mass suicide. Child-rearing is left to the other clan of the commune, or else to chance. Most anilins are fatalistic about their ultimate end, but some seek the secrets of longevity, and other then men they are the chief students of gerontology.

Anilins worship nearby nature spirits or else appease whatever gods they deem local to them. The anilins also revere the Everlasting, a clan of anilins who were wished immortal through the sacrifice of many other clans. The anilins ask them for guidance and wisdom, though they do not often answer, and none have been seen in living memory, for their numbers have been greatly reduced by violence.

Kinnots

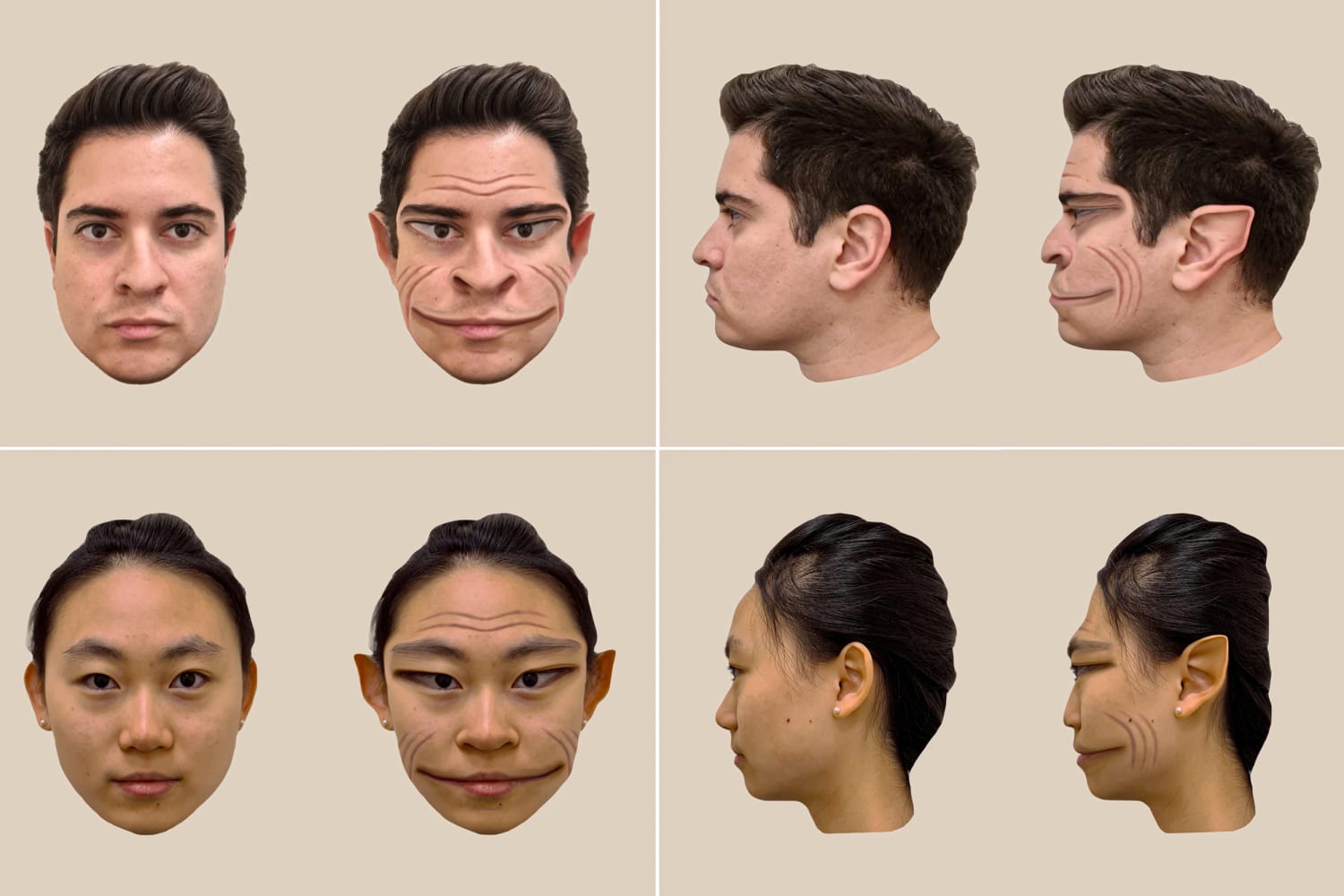

If you’re lucky, you’ll see them moving – they don’t move like anything human. They switch between moving too fast to standing eerily still, but you won’t notice when you first look at them. They look like slim humans, their wide, articulated ears are the only giveaways on their silhouettes, and they know to cover them with hoods.

If you’re close enough to see their face, then you’re probably already dead. Their mouths and eyes are stretch back towards the sides of their face, their cheeks and foreheads nothing more than a series of creases. Their wide noses often bear bone ridges, and artificial piercings. Their pigmentation is wildly divergent – spots, brindling, and strange colors are endemic. Their teeth are made exclusively for tearing flesh – the flesh of men.

Kinnots are the favored pets of the elves of old. The were bred and trained to hunt the early tribes of man, and their ability was so great and terrible that to this day the serve as boogeyman in old tales and fables. Their numbers are so diminished that few humans now recall they truly exist.

The nuclear family is their basic (and only) social unit – parents and their children. ‘Children’ in this case means under sixty years – these were the pets of the elves, so they can live up to three hundred. A kinnot matures at the same rate as a human, so the sixty-year cutoff is just when they split off to form their own mating pair and pack. Of course, this assumes they live that long – their lives tend to be brutal and short for several reasons. First, they normally live in the peripheral wilds, with all the dangers that entails. Second, they are forced into ecologically marginal lands by humans, so starvation is common among their population. Third, they can’t truly avoid humans – they aren’t natural survivors, so the still need things like clothes, weapons, and tools to live in the wilderness. They usually lack the means and/or skills to make these themselves and steal them from humans, adding to their mythos. Also, though they can survive on any meat, many do prefer human meat. Most won’t hunt humans since that would make them targets, but sometimes children wander into the woods, and other times hunger overcomes prudence. Lastly, while kinnots will never fight their parents, siblings and other kinnots are generally fair game. Typically, one party ends up dead and the other maimed.

Parents will try to prevent these fights, but they can’t watch their children all the time, so it’s an accepted social truth that some of their children will kill each other. This also goes for pack meetings – usually it’s understood that they should go their own way, but they’re always ready to kill each other. If you ever seen two cats fight like they mean it, then you basically understand how a kiniho fight usually goes. A lot of rolling, jumping, screeching, hissing, happening too quick to watch, since their reflexes, speed, and strength far outstrip human capabilities.

This is a marked difference from how they hunt humans or other prey. A kinnot fighting another kinnot is a fair fight. A kinnot hunting a human is like an eagle hunting a mouse. In addition to being twice as strong and fast as a baseline human, they possess a keen array of senses: better than perfect vision that stretches into the infrared, ultrasensitive hearing, and hunting-dog level smell. In addition to these, they posses several supernatural abilities. If a kinnot covers one eye and locks the other one with a human, they can ‘eye-lock’ and see out of the human’s corresponding eye, but with the kinnot’s visual acuity. Blocking the other eye robs the human of sight. They can even eye-lock without a human noticing they locked eyes – a kinnot’s eye looks like undifferentiated green-brown iris and reflects almost no light. They are also talented ventriloquists, and capable of perfectly imitating any sound they’ve heard more than once or any human voice they’ve heard at all. Skilled ventriloquists can throw their voice to make it sound like a voice is coming from inside a human’s head if they’re close enough, which they call ‘back-speak.’ Eye-locking and back-speaking can be combined by the older and more experienced kinnots to ‘mind-bait,’ which basically cracks down to imitating a human’s inner dialogue. This can either be used as a form of low-level hypnotism, or convince the human they’re going completely insane.

The kinnots’ entire suite of senses and abilities is designed to fuck with humans and make them easier to kill. A human’s best sense is usually sight, so the kinnot hunts by night and can use it themselves or take it. Humans use sound to communicate, so the kinnot uses ventriloquism to fool them. And humans are stronger in a group – an advantage kinnots never have – so they use mind-baiting and all their other abilities to separate and kill them. Even without permanent settlements or a continuous culture, kinnots are a deadly foe even for a human party ten times their size.

Actually, I tell a lie. While they don’t have much in terms of material culture, they all speak various forms of degraded Elvish, so they can usually communicate with each other and many humans. The art of snares, poisons, and potent paranoia-inducing hallucinogens has been passed parent-to-child for many generations. The art’s survivability can also be accredited to many of the ingredients being derived from kinnot bodily fluids. The hallucinogens in particular enhance the range and abilities of eye-locking, allowing a kinnot to ‘transmit’ hallucinations to the human’s sight. They love javelins for both hunting and sport, even though the only ones they cna themselves are crude wooden examples.

There are legends that after the extinction of the elves, some kinnots learned to use illusion magic* and became deadlier than ever before. Some say that kinnots are smarter than humans, which is why they made such talented illusionists, but in general they’re only more single-minded and focused. A kinnot is a fully-dedicated student of anything that makes them better at killing or surviving. Their focus is so legendary that fables depict them running after prey until they collapse from starvation or dehydration, never noticing hunger or thirst until their bodies fail. Anyways, the general consensus is that their probably was some kind of order of highly-advanced and even-more-magically-enhanced kinnots, but they were destroyed by an order of blind ascetics. A conspiracy among the more hysterical supporters of kinnot extermination posits that the Illusionist Kinnots were never defeated, but instead became such effective illusionists that they have entire hidden cities and use their magic to pull the strings of power.

Thankfully, kinnots have a single glaring weakness – they are deathly afraid of fire and are quickly killed or blinded by it. While kinnots sometimes run themselves to death in pursuit of prey, they can also sometimes run themselves to death fleeing flames. Humans think this is a natural flaw or a form of kill-switch built-in by the elves, but kinnots claim it is the result of a congenital curse placed on their race by early man as revenge for the hunts against them. Kinnots can certainly move during the day without suffering death or blindness, so there is some credence to the curse idea. Wildfires are the weapon of choice for driving kinnots out of the wilds.

Kobolds

Kobolds are mimics and cowards. Their evolutionary ‘strategy’ is based on imitation of much more vicious and scary animals, or else running away. In the common juvenile form they resemble a large reptilian predator – alligators, crocodiles, and dragons. No human will ever confuse a juvenile kobold for a dragon, even a young one, but a tiger might pause.

Despite their reptilian appearance, the larger kobold lifecycle that few humans ever witness has more in common with insects:

Egg —> Larva —> Pupa —> Juvenile —> Chrysalis —> Adult

Kobold eggs are delicious but otherwise not noteworthy – this the only part of the lifecycle that doesn’t imitate anything else. Kobold larvae are wormlike-grubs that burrow into flesh, mud, or feces. They are mostly helpless and also delicious, but tend to resemble the larval forms of dangerous, poisonous, or disease-ridden insects. Just don’t fall into a pit of them – they’re hungry and can strip flesh very quickly. They are also smart enough to hide themselves from predators, or while pupating into a juvenile. Inside the pupa, the larval kobold will essentially dissolve and reform itself into a small version of the juvenile form. This intermediary liquid is an aphrodisiac and general panacea, but is difficult to extract, and complicated by the aforementioned mimicry – it’s so effective that even experts only have even odds of properly identifying one.

The juvenile stage is the lizardy, draconid gremlins most humans are familiar with. They scheme, build warrens, steal pigs, sometimes practice agriculture, lay traps, and cringe in fear. They are as smart as humans, if more prone to anxiety. They also give live birth to more kobold juveniles, so the lifecycle has a built-in redundancy loop. Only the rare adult kobold can actually lay eggs, and even those are soft-shelled – the many discarded egg fragments found throughout kobold dens are the result of their dietary habits.

The chief concern of a juvenile kobold is hoarding food. It’s a compulsion for them. If it’s organic, or even looks like it might be edible, they’ll probably try to collect it. Most of what a kobold collects ends up going to the kobold boss(es). The boss is usually a singular juvenile that for whatever reason is smarter, stronger, more charismatic, luckier, or some combination thereof. Their rule tends to be vulnerable to challenge from other juveniles – kobolds are not obsequious by nature, but for obvious reasons the bosses tend to value subservience. The stereotype just ended up sticking. Sometimes many kobolds form a class of bosses to order around the other juveniles, but these arrangements also tend to be unstable, as the adult stage they are trying to reach is powerfully solitary regarding other adults. Kobold bosses need to eat as much food as possible to grow bigger, and once human-sized they can form their chrysalis (which their servants help to build out of their spit, which they also sometimes use for other structures; kobolds are gross) and start gestating into an adult. The chrysalis is usually about the size of a house, and kobolds have to fill it the rest of the way with more organic material. Usually, this is peat or some other kind of fossil fuel, but kobolds have also been known to baby-bird chewed up food into the chrysalis. Once again, the kobold will basically dissolve into goop while they form their adult bodies.

The whole process from takes about a decade, and the kobold-chrysm is among the most sought after alchemical ingredients in the world – it can transmute anything into almost anything else, permanently. Using it to turn lead into gold would be a waste; the chrysm is worth more than its weight anyways. Many, many kobold warrens implode at this stage because the underlings decide it’s easier to sell of the chrysm then babysit their asshole boss for a decade, and it’s the reason why there are very few kobold adults. But if the process does work, then the chrysalis will crack open to reveal a house-sized wingless dragon, most of the time. In truth the kobold adult will take on features of things they ate, if they ate a lot of it. These features are passed onto any kobold children the adult has, is why you sometimes see kobolds with wings, mammalian traits, hyperintelligence, photosynthetic skin, or other ‘nonstandard’ features. Even at this late stage, the kobold can’t quite shake their mimicry habits, although it would be a mistake to assume this is still their main survival strategy. The kobold adult will wake up ravenously hungry, and will eat the rest of the warren if they haven’t prepared properly, along with anything else in the area. Adult kobolds never stop growing, and soon grow from the size of a house to the size of an actual dragon and beyond. After the initial feeding frenzy, they’ll hibernate to avoid starving themselves, and during this time they’ll lay eggs, giving birth to a new brood of kobolds to run around and gather food for them. The adult will continue to grow, just at a slower rate, and any humans nearby are wise to take steps to prevent the kobolds from practicing agriculture (and kobolds are very efficient agriculturists when they are allowed to practice it) or other methods that increase their caloric surplus. Sometimes, kobold oblige the humans by feeding the adult as little as possible, or splitting off to form their own warrens. They aren’t innately loyal, after all. If the adult grows too fast, it will lay more eggs, which means more kobolds and probably more land under cultivation, which means more food. If this goes on long enough, the adult might wake up entirely, which means conquest, rampaging towards more fertile lands, or just rampaging in general depending on how intelligent the adult is.

This is bad for the humans and frequently bad for the kobolds as well (they might get eaten, drafted into war, or pressed into backbreaking labor) so between intermittent warfare and self-regulation, the two races basically reach a sort of ecological equilibrium. The low growth rate maintained by the food the kobolds can find in the wild or steal from humans is slow enough to keep the adult in hibernation (or prevent an adult from emerging) and keeps the kobold population under control, without the humans having to go out of the way to try to exterminate the warren. While kobolds are smaller and weaker then humans, they focus their efforts in defensive tactics, attrition, feints, and especially trap-setting. Kobold fables and parables could be compiled into their own Art of War, if they had writing*. That’s to say nothing of the adult, which is probably at least as large as a dragon, and probably harder to kill. They’re so chock-full of redundant organs that it’s hard to meaningfully harm them, and they also regenerate – slower than trolls, but fast enough to notice. This makes them easy to manage but hard to get rid of, unless they spread out and start farming. Kobolds stealing your pigs is a nuisance – kobolds planting crops is a prelude to natural disaster.

*because of their need to manage large surpluses, many kobold warrens have developed numeracy and record-keeping, although this doesn’t appear to have gone on to language.

Sure, even at the slower growth rate, the adult will eventually wake up and start moving and destroying everthing around it. But that happens irregularly and almost never more than once every 100-150 years, so on a human timescale it’s an acceptable risk. The exception is the ‘final’ stage of the kobold lifecycle. Scholars disagree on whether it’s a separate stage, a kobold affect by gigantism, or merely an adult that managed to grown mountainous size. If it is a separate stage, only one case of a kobold reaching it is known, and it’s only woken up twice in recorded history. It’s called the Tarrasque, and when it rouses the world can do naught but bear witness as it grinds entire cities and kingdoms beneath its palatial claws.

Categories: Uncategorized

it’s a good post gamer

LikeLiked by 1 person